Tiger Tales

Rajita Banerjee

Introduction

The tiger prowls far beyond its jungle home, and the world currently recognizes six subspecies of tigers. Some subspecies, have unfortunately not been able to stand the test of time, and have gone extinct. These include the Bali, Caspian and Javan tigers. The creature sprawls across the high-gloss runways of the world in coats patterned after its stripes, its likeness roars from brand logos, and its name is stamped onto jars of medicine, sports jerseys, and luxury goods. Like the cheetah’s spots, the tiger’s stripes have become a recurring motif in fashion, symbolizing danger, elegance, and untamed beauty. The tiger’s stripes — knit into sweaters, woven into jacquards, and printed with bold elegance — have long been a source of inspiration for designers (see Vogue’s feature on how the tiger and its stripes have inspired fashion designers). In popular culture, the tiger is everywhere: a mascot for speed and strength, a talisman of good fortune, and an emblem of power. Yet behind the glamour lies an older, more primal truth. This is an animal both revered and feared — worshipped in temples alongside goddesses, immortalized in folklore, depicted in local artforms and dreaded by those who share its territory. It is the apex predator, the “beautiful beast,” carrying centuries of myth and memory on its back. But in the wild, the tiger’s story is one of loss and fragility — a life under siege even as its image thrives.

Tiger as the Ambassador: The Tiger in Brands

The tiger has long been a favorite motif for brands across the world, a creature whose stripes suggest both elegance and danger, whose power lends instant recognition to a logo. From sports mascots to energy drinks, designers have leaned on the tiger to signal ferocity and confidence. Yet beyond the generic uses of the animal as a symbol of strength, there are certain brands for whom the tiger is more than a decorative emblem — it becomes a story, a lineage, a philosophy. Two such examples are Tiger Balm and Sabyasachi, which in very different ways capture the tiger’s aura of trust, heritage, and cultural meaning.

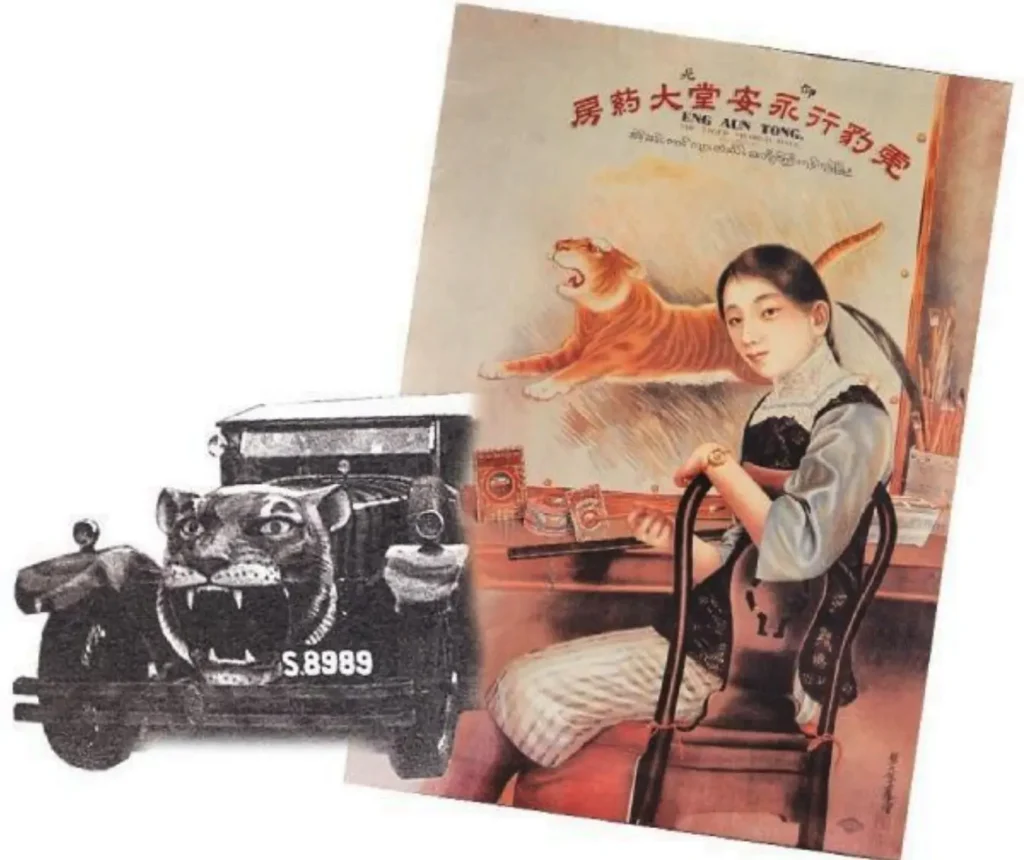

The story of Tiger Balm begins not with modern marketing but with a family recipe refined by two brothers, Aw Boon Haw and Aw Boon Par, in the early twentieth century. Boon Haw’s name itself meant “gentle tiger,” and that feline identity was built into the product from the beginning. The now-famous hexagonal jar, with its red and gold colors and prowling tiger insignia, became more than packaging—it was a guarantee of authenticity, a visual shorthand for reliability across generations. While countless consumer goods have gone through cycles of reinvention, Tiger Balm’s strength has been its continuity: the logo and the story it tells reassure users that this small jar carries a heritage that blends Chinese and Western herbal wisdom, tested and trusted in households around the world. The tiger, in this context, stands not for menace but for endurance and healing power.

[Poster for Eng Aun Tong Pharmacy, which produced Tiger Balm. Sourced: https://www.tigerbalm.com/us/heritage/]

Sabyasachi, by contrast, transforms the tiger into a symbol of cultural luxury and postcolonial pride. The couture house has adopted the Royal Bengal tiger as its insignia, a conscious act of rooting the brand in South Asian identity. To wear Sabyasachi is not only to wear painstakingly crafted garments but also to carry an emblem that gestures to mythology, history, and national symbolism. The tiger in Hindu iconography is the mount of the goddess Durga, a divine force of both ferocity and protection. By placing the Bengal tiger at the heart of his brand, Sabyasachi invokes this layered heritage—drawing on South Asia’s ecological and spiritual landscape to frame his designs as more than fashion, as a philosophy of cultural continuity. From the hand-engraved Bengal Tiger Necklace that cradles an emerald to entire capsule collections that weave tigers into lush tropical tapestries, the animal becomes the guardian of a certain vision of India: luxurious, historical, and unapologetically local while still appealing to global eyes.

[The logo for Sabyasachi. Sourced: https://www.adityabirla.com/businesses/brands/sabyasachi/]

That the tiger resonates in both these brands — one a medicinal balm born in Southeast Asia, the other a high-fashion house from Kolkata — speaks to the animal’s extraordinary symbolic elasticity. It can stand for comfort and trust as much as for ferocity and magnificence. It can be packaged in a pharmacy jar as well as a couture necklace, and in both cases the presence of the tiger deepens the object’s meaning. For collectives such as ours, too, the tiger remains central, a reminder that the animal is not just a motif but a cultural force—one that continues to guard, to inspire, and to define how South Asia sees itself and how it is seen by the world.

To be Feared and Respected: The Lore of Bonbibi

In the tangled estuarine forests of the Sundarbans, where land and water blur into one another, the tiger is not just an animal. It is an actor in a mythic drama that pits human survival against the deep, unpredictable forces of nature. Nowhere is this more evident than in the cycle of tales surrounding Bonbibi, the forest goddess, who is invoked by Hindus and Muslims alike for protection against tigers.

[map of the Sundarbans. Sourced: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Map-of-Sundarbans-India-Bangladesh_fig1_359292395/]

According to the Bonbibi Jahuranama, composed in the late 19th century by Munsi Mohammad Khater, Bonbibi was sent by Allah to safeguard the “eighteen tides” — the low-lying lands of the Sundarbans. She arrived with her twin brother Sajangali to challenge the domain of Daksin Ray, a powerful landlord-deity associated with wealth, honey, timber, and above all, with tigers. The tale recounts Bonbibi’s battle with Daksin Ray’s mother Narayani, who unleashed armies of witches, ghosts, and spirits to repel the newcomers. Armed with the kalema (the words of faith), Bonbibi overcame these demonic forces, establishing her authority as guardian of the forest.

What makes Bonbibi remarkable is not only her triumph over tigers and spirits, but the way her story reflects the imagination of the people in Bengal. As Tony K. Stewart argues, these narratives occupy a discursive realm where imagination and cultural memory intersect. They are not historical chronicles but fictional worlds that are responsible for creating their own truths — shaped by local geography, oral performance, and the anxieties of those who lived at the forest’s edge. For villagers venturing into the mangrove swamps to collect honey or wood, Bonbibi became both reassurance and warning: honor her, and the tiger will let you pass; forget her, and you may not return.

[Depiction of Bonbibi. Sourced from: https://www.livemint.com/mint-lounge/ideas/keeping-faith-with-bonbibi-111641418675231.html]

This duality — reverence and fear — is at the heart of the Sundarbans’ relationship with the tiger. Tigers here are not merely predators but emissaries of Daksin Rai, “lords” of a domain where human claims to mastery falter. The tales function as cultural tools that help people make sense of the world around them: by embedding ecological danger into sacred narrative, they regulate human conduct in perilous terrain. They also blur religious boundaries — Bonbibi is revered in Muslim texts and Hindu performances alike, making her a figure of shared pluralism even in contested cultural landscapes. Today, Bonbibi’s story lives on not just in village recitations and performances, but in literary retellings like Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide. There, as in the oral tradition, she remains the axis around which the human-tiger encounter turns — a reminder that the tiger is never just an animal to be studied or feared, but a presence woven into the fabric of cosmology, faith, and daily survival.

A Symbol of Anti-Colonialism

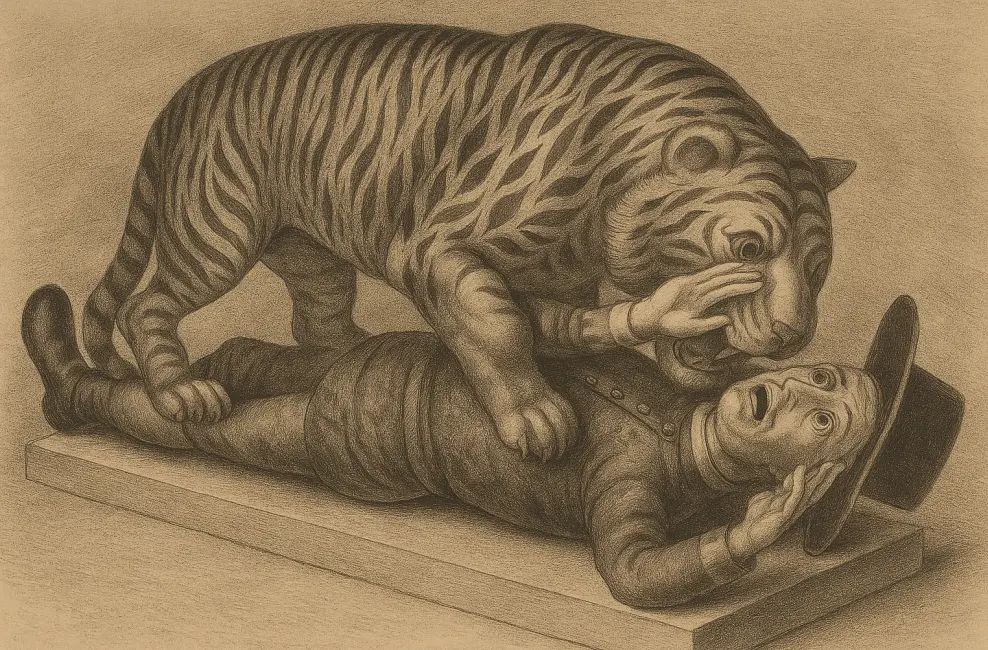

[Tipoo’s Tiger: An exhibit that can now be found at the Victoria and Albert Museum]

The tiger, native to sprawling landscapes across Asia—from the dense Sundarbans to the Siberian taiga — has long embodied the identity, pride, and spirit of the countries it inhabits. Yet when colonial powers entered these regions, the tiger was recast. British officials and aristocrats treated hunting it as a rite of dominance: a widely recorded ritual of conquest that underlined imperial masculinity and civilization’s supposed mastery over nature. Lord Curzon, for instance, famously hunted tigers across princely states including Gwalior, Rewa, Hyderabad, and Cooch Behar, with photographic trophies showing him standing triumphantly over his kills. In the jungles of the Raj, tiger hunting evolved into a highly orchestrated spectacle—hunts conducted from elephant back, accompanied by beaters, elaborate logistical preparations, and ornate rifles—a ritualistic manifestation of power and control.

[Lord and Lady Curzon Pose After a Hunt in Hyderabad: sourced: https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13887997]

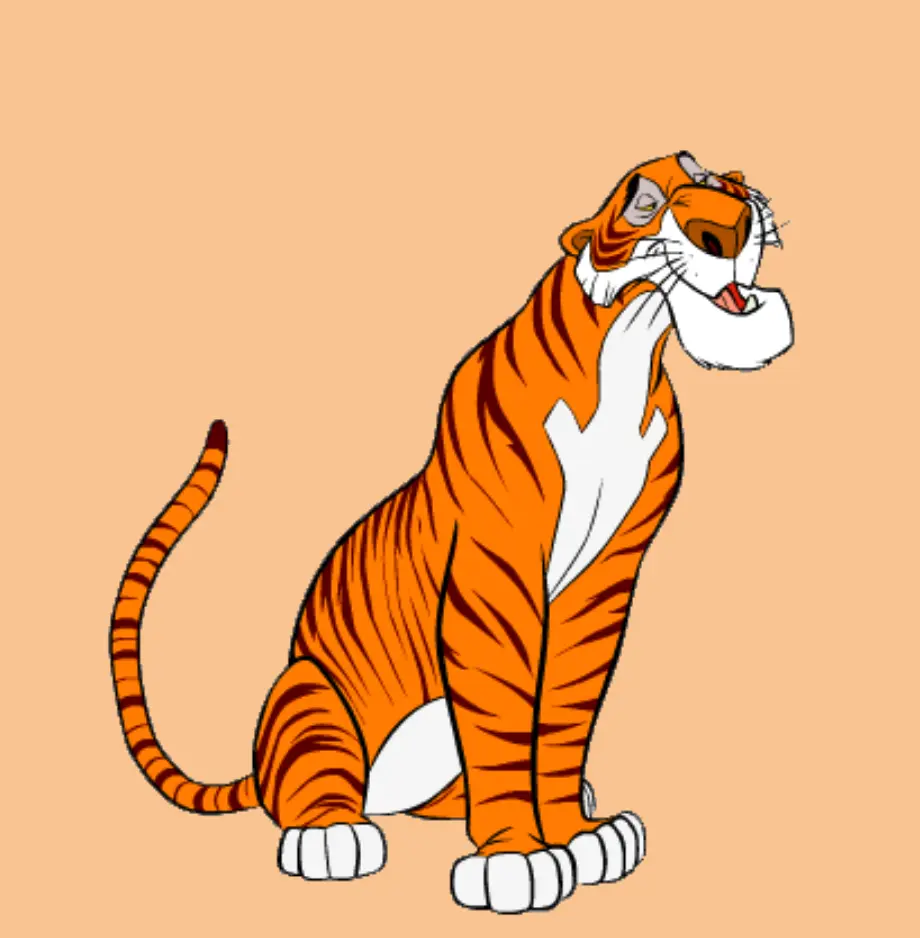

This colonial lens also bled into literature. In The Jungle Book, Rudyard Kipling’s Sher Khan—a regal, fearsome tiger—is depicted as a symbol of wild savagery, a force to be vanquished or outwitted by human intelligence. Such narratives mirrored the colonial worldview that sought to suppress and tame indigenous nature, turning the tiger into a metaphor for wilderness that must be subdued.

[Sher Khan in The Jungle Book. sourced: https://walt-disney-animation-studios.fandom.com/wiki/Shere_Khan]

The Threat of Extinction: Dangers to the Cats

The tiger’s story in the modern world is a paradox. It is an animal celebrated across cultures, immortalized in myth, and branded on everything from sports jerseys to fashion houses, yet in its native forests the species has been brought to the edge of extinction. The twentieth century saw their numbers collapse from nearly 100,000 individuals to a few thousand, decimated by hunting, habitat destruction, and the insatiable demand for their bones, skins, and other body parts. By 2010, global estimates suggested that only around 3,200 wild tigers remained — a low point that forced governments, scientists, and conservationists to reckon with the possibility of losing this emblematic predator altogether.

Research from the 1990s had already laid bare the fragility of tiger populations. John Kenney and his colleagues demonstrated in 1995 that even modest levels of poaching could send tiger populations into a downward spiral, where a few additional losses pushed them into what they termed a “critical zone” of rapid decline. Worse still, their models showed that once a population is depleted, even stopping poaching does not guarantee recovery: genetic variability shrinks, leaving tigers vulnerable to inbreeding and random environmental shocks.

In the 2000s, debates flared over the idea of tiger farming as a supposed solution. Advocates argued that breeding tigers in captivity and releasing their parts into the market could reduce pressure on wild populations. But conservationists countered with strong evidence to the contrary. A 2008 study warned that farming tigers would do nothing to curb demand for wild products, which are cheaper to obtain and seen by consumers as more potent. Two years later, in 2010, researchers Craig Kirkpatrick and Lucy Emerton dismissed the farming argument as a “fallacy,” showing that markets for tiger products were far from rational or competitive. Instead of reducing demand, they argued, farming would likely increase it, just as bear bile farming had expanded consumption rather than replacing wild sources.

Despite these warnings, conservation efforts began to take hold. Protected areas were strengthened, law enforcement expanded, and international bans on trade were more vigorously enforced. The results are visible today. According to the World Wildlife Fund, there are now about 5,574 wild tigers across their range — a fragile but hopeful recovery from the historic low of 2010. Much of this growth has been driven by India, which now holds nearly three-quarters of the global wild tiger population, rising from 1,411 tigers in 2006 to 3,682 in 2022. Nepal, Bhutan, and Russia have also reported steady gains, while ambitious reintroduction projects are underway in places like Cambodia.

Still, the recovery is uneven. In parts of Southeast Asia, tigers remain under severe threat from poaching and habitat loss, and illegal markets for skins and bones persist. Recent investigations have revealed tiger farms in South Africa supplying body parts to Asia, proving that the risks of commercial exploitation remain urgent. The species now occupies only 7% of its historic range, and every gain is hard-won and precarious.

The lesson across decades of research and conservation practice is consistent: there are no shortcuts. Farming cannot replace wild protection. Trade bans must be upheld. Strong governance, political will, and long-term ecological commitment are the only paths forward. The rebound to 5,574 is not an endpoint but a reminder — that with vigilance and vision, the “beautiful beast” can continue to walk the forests of Asia not as a relic of memory, but as a living presence.

[Alternative AI generated image, based on Tipoo’s Tiger]